Fort Worth Blues, 11/14-15/2024

Months before, when I bought the tickets, I was concerned about the dates and how I would feel. The first was for T Bone Burnett at a local listening room in my Dallas neighborhood called the Kessler Theater, and the second the next night for Leon Bridges and Charley Crockett at Dickie’s Arena, where they hold the annual Fort Worth Stock Show and Rodeo. The two dates fell on a Thursday and Friday, the week after the election. Would I be elated, my trust in the American electorate renewed? Or—well, we all know how it turned out.

Both shows advertised the artists’ local connection. Burnett and Bridges were raised in Fort Worth; Crockett lived as a youth and started playing music in Dallas. All three had achieved success across the nation and overseas, and now they were “coming home.” But America had failed a test of character, of faith, and the atmosphere at home was heavy with dark portent. Would the artists acknowledge the situation? Could they?

For a moment I wondered if I’d even be able to attend, but I did go, pushing through the gloom. Everything I saw and heard was full of commentary. But all the while I couldn’t tell whether I was projecting this commentary on events, or whether what I saw and felt was really there.

On Thursday, just before the show started, an announcement came over the system requesting that all phones be turned off and put away. Then T Bone Burnett came out on stage to speak at length in explanation. The smartphone, he said, has made people too reliant on their eyes, and they’ve neglected their ability to listen. Burnett is seventy-six years old, but this wasn’t simply some old-guy rant about how much better things used to be. It was a fully digested and interdisciplinary discussion delivered with supporting citations that included Jacques Ellul’s The Technological Society and Ian McGilchrist’s The Master and His Emissary. According to McGilchrist, Burnett explained, before there was language, people communicated by singing. Empathy and understanding were conveyed largely by tone. Now people communicate via hand-held machines that they stare at, with the result that their more profoundly evolved social sensitivities have shriveled. The phone ban was to promote more and better listening. An audience member called out to ask whether they might be allowed to take a single photograph. Burnett smiled and declined the request.

Who the heck is T Bone Burnett, a reader may be asking, and where does he get the cojones to make such a demand? It’s a fair question. For decades now, Burnett has worked mostly behind the scenes in the industry, not as a performing artist but as a producer and soundtrack coordinator for television and film. He has overseen many legendary recordings, notably the O Brother Where Art Thou soundtrack. Burnett can be considered a founding father of Americana, a music genre created in the late-1990s to market a vibrant but diffuse roots music revival. Now Burnett was touring his own record, the first in a long time, and for most in the room he was a beloved figure whose ruminations carried weight.

To sit for a concert and never once glimpse the light of a phone was novel, to say the least. But I resisted his call for better listening. In the immediacy of the moment, it sounded like the old admonition that Democrats need to listen to MAGA America and hear where they’re coming from. No, no, no, I thought. We heard them loud and clear, and it was frightening. “From here on out,” Burnett later said, “all I want to do is create.” In this I heard my own desire to isolate, to devote myself to private interests—to turn off, not only my phone but anything that might convey further news of our collective disaster. I heard in Burnett’s words other words I’d heard during the past week or thought in my own mind. “I don’t want to protest, I don’t want to march, I just want to wait it out, and maybe it won’t touch me.” “Life has always been absurd.” These sentiments are understandable—easier for certain demographic groups—but understandable.

No doubt, Mr. Burnett, I was listening. But in the context of events, maybe I was hearing more than was being said. Or maybe what I needed to hear could only be communicated in code. I was certain, for instance, that at Dickie’s the next night, Charley Crockett would open with one of his new songs, “America.” It isn’t one of his best songs, but it’s so on the nose that it would have been perverse not to foreground it, just out of sheer obviousness.

America / how are ya?

I hope you’re feeling fine

America, I love ya

But I fear you sometimes

The last line resonated. It was how I’d been feeling all year. If you paid any attention at all to the rhetoric of the winning campaign, how could you not but feel afraid? Yet if the vote count had come out the other way, wouldn’t the MAGAs be feeling fear, too? For four years they’ve been fed visions of murderous immigrants, trans women haunting restrooms, gender surgeries performed at public schools, delivered babies promptly executed, and on and on and on. The very point of that demonizing rhetoric was to generate fear and to mobilize it politically.

Crockett plays a blues-country-soul-folk mixture so perfectly blended that generic labels fail to describe it. And yet he’s had to market himself as “country” to reach a wider audience and not just appeal to the fanatics on the fringe, such as myself. To reach that wider audience, he’s had to be careful what sort of politics he signals. At the same time, as an artist, he has to speak from the heart. I like to think his heart is with the social-justice camp. This impression is not wholly a product of wishful thinking but based on a podcast interview he did back in 2018 at the start of his upward trajectory. In the interview, he praised Texas’s demographic diversity and aligned himself with the Willie Nelsons and Barbara Jordans of our state. Now that he’s selling out theaters and auditoriums across the country, he can’t do that anymore, not if he doesn’t want to be Dixie-Chicked by what must now be a substantial portion of his fan base.

This is what made “America” such a perfect opener.* It acknowledged the moment; it was honest. It exemplified how well he’s crafted a working-class persona while walking a political fine line. Yet for me, on this particular night, after that particular week, Crockett’s tightrope trick read as too even-handed.

And then there’s the more troubling chorus:

America, forgive me / I’m only a man

Forgive you for what, your vote? A large percentage of men voted with their gender over any concern that the women and girls in their lives had lost rights over their bodies that they’d fought for and won half a century ago. Even if not read so specifically about the Dobbs decision, the conceit is an old one in the country and western songwriting tradition: To play the victim in romantic relations, to pretend all the power is held by the woman so that when things go wrong, she can be blamed. In this case, the woman is America. Forgive me, the singer pleads, for being so powerless and so wronged. It rings false, this posture of humility, coming from a male within a retrenched patriarchy.

Still, Crockett was only the opening act. This was Leon Bridges’ night. I last saw him years ago in Dallas, after his first album of sweet, throwback soul had taken off. He was winding up a national tour. The songs benefitted from the road wear; the band had made them their own. Bridges bounded from one side of the stage to the other. This time, I expected more of the same. He had, after all, sold out a 14K-seat arena in his hometown. But throughout, Bridges struck me as subdued. He opened with the first song on the new record: “(This is What it Sounds Like) When a Man Cries.” Again: relevant. Again: more gender games. Yet this time the “you” in the song seemed more sharply aimed at those who were celebrating our tears:

Why I gotta see them things that hurt my heart?

Feel my world split in two

I know you hurt so bad / You gotta hurt me

Hate what the world has done to you

Was I right to read this as a message to the MAGAs—their grievance politics, their left-behind economic status, their vote for revenge, to burn it all down, out of spite? Sure enough, a line from the second verse seems to make exactly this point:

Say you wanna start a fire to see how it feels

To see who we are when they burn?

Toward the end of the show, Mayor Mattie Parker came onto the stage to offer Bridges the proverbial key to the city. From this day forward, she proclaimed, November 15th would be known in Fort Worth as Leon Bridges Day. Parker is a Niki Haley Republican, which can be seen as either a principled position or a politically savvy one in the only Texas city that votes purple rather than solid blue. As she stood beside him, I couldn’t help flashing on the scene from—yes, Oh Brother, Where Art Thou?—when the rotund governor climbs onto the stage to horn in on the love a large audience is bestowing upon The Soggy Bottom Boys, who have just performed their surprise hit, “Man of Constant Sorrow.” The governor is running behind in his bid for re-election and recognizes an opportunity in the gob-smacked crowd.

I thought I saw discomfort in Leon’s face as the mayor hugged him close for photographers. Given that his actual face was two floor sections distant from where I was standing and that the face I saw discomfort in was projected upon a pair of giant screens flanking the stage, it’s possible that my own discomfort was likewise projected. It is a design flaw in the human construct that we saturate the incoming data with our inner storms. The distortion of reality that results can only be counter-balanced by a constant, Puritan self-surveillance of the sort that threatens to suck all the joy out of life.

This time, though, I’m going to stand by my gut feeling that the drama was real and that Bridges and I were in a similar head space. Toward the end of his set, he played another new song: “God Loves Everyone.” Again, for anyone bruised by what had occurred the previous week and frightened by an ascending authoritarianism, the lyrics fit the moment well.

God loves the birds and the bees / God loves the stoners and freaks

And the girls on the street / Just the same as you and me

Old men and the young and the strange / School kid looking out at the rain

Cops on the beat and the crooks in the cage / Just the same

Merely a coincidence, you say? A coincidence, and not a case that the man on stage had chosen this song as commentary, as balm for the hurting? Merely a coincidence, you say, because it was a song recorded months ago, for an album the setlist was designed to promote, its title on t-shirts and pullovers for sale at the merch tables out front? No, I say, not merely a coincidence. The election results did not arrive out of nowhere. We’ve known this politics of division, punching down, and hate since the beginning, and this current version for more than a decade.

Driving home I remembered something else T Bone Burnett said the night before: The promise of America is realized in American music. Listen, he said, to the music of Indigenous Americans. It keens like the music of the Scots Irish. Its rhythmic movement plots with that of the Mississippi blues. And the pedal steel guitar, that representative sound in country music—it came from Hawaii. Burnett’s claim is neither new nor original, but it’s probably not articulated enough. American music is where the boundaries break down, and we listen to each other. I don’t mean the American music business, which is just as rife with institutional bias as anything else in this nation, but the music itself: e pluribus unum. Feeling as raw as I was, Burnett’s riff brought a tear to my eye. Maybe all is not lost. While we gird ourselves again to defend our best ideas, they are there when we need them, safe in songs.

This essay appeared in the Society of US Intellectual History blog.

_____

* It turned out Crockett didn’t open with the song. He clo

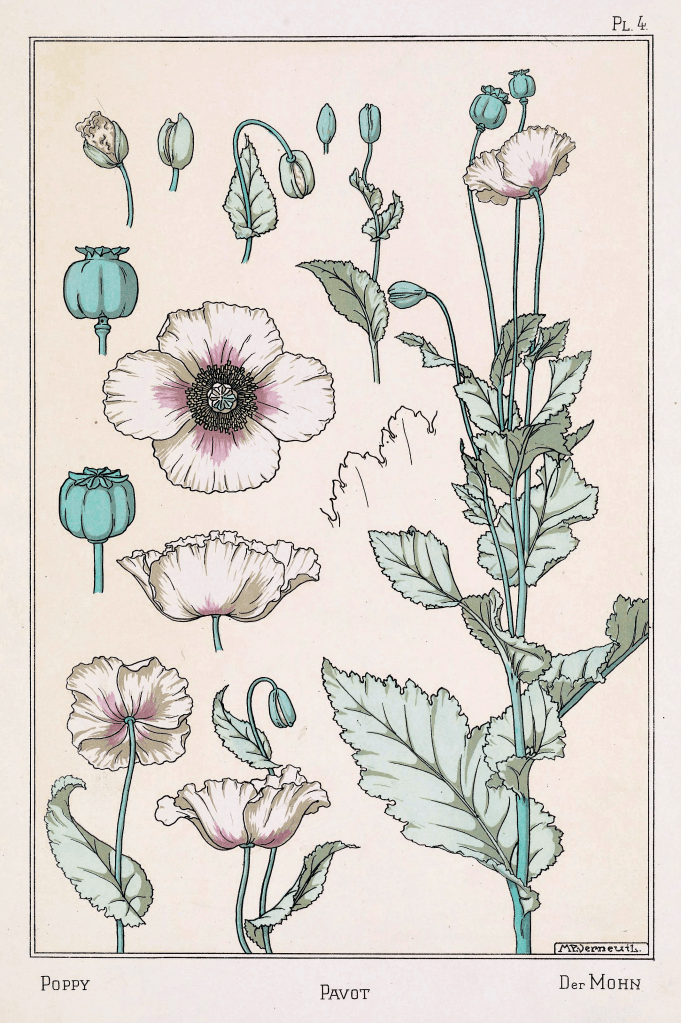

The Poppy Acts: the agency of the non-human in Amitav Ghosh’s Smoke and Ashes

Once in a while, even in works of popular history, an author will raise the prospect that what happened twelve thousand years ago, during the so-called Agricultural Revolution, wasn’t that humans domesticated plants but that plants domesticated humans. From a Richard Dawkins ‘selfish gene’ perspective, this makes a kind of sense. To ensure the survival of its DNA, a plant was shrewd to offer itself up as a staple to the human diet. Armies of human slaves were soon organized and trained to cultivate and protect generation after generation of its offspring.

Authors mean this as provocation, I suppose, something perhaps to get the mental juices flowing, because the idea is typically dropped just as soon as it’s floated. Of course it is. To explain the Agricultural Revolution as the botanical domestication of human beings would be to attribute historical agency to plants, and what is that if not blatant superstition?

Yet the granting of historical agency to non-human subjects and the exploration of what such a radical prospect would mean to our understanding of the past and the present has been the project of Amitav Ghosh, one of the most influential and compelling scholars writing in the humanities today. In his latest book of non-fiction, Smoke and Ashes: Opium’s Hidden Histories (2023), Ghosh excavates the British empire’s nineteenth-century Asian opium monopoly: its cultivation and processing of the poppy nectar in South Asia, its importation and distribution into the ‘virgin soils’ of Southeast Asia and China, and—because, without this trade, the empire would not have been fiscally viable—the violence that it used to establish near total control of the many aspects of this enterprise, including two Opium Wars. Ghosh examines the trade’s literature and visual arts, its arguments of justification and dissent, and its legacies and parallels in the present day.

Among these legacies are those parts of India, relatively more stable and less blighted with poverty today, where particular peoples were able to skirt British dominance, to maintain degrees of autonomy, and to find their own ways of profiting from a highly lucrative market in a highly addictive drug. Among the parallels is the opioid crisis of recent decades in the United States. In this historical rhyme, the British role is played by Purdue Pharma and the Sackler family, the Chinese by the working class of deindustrialized America, and the precisely weighted packets of smoke-able Chana by machine-cut tablets of OxyContin and Vicodin.

All well and good. All quite thorough and impressive, actually. But here’s the difference. Ghosh believes that this history is best understood by perceiving the poppy plant not as inert matter, but as “an actor in its own right,” an “independent biological agent.” I see the reasoning for this approach. Ghosh is not alone in taking the position that the consequences of modernity, which we now must recognize as dire and catastrophic, were built on a fundamentally modern orientation that attributed intelligence solely to the human mind and dismissed the remaining non-human world of life as mindless, biological mechanics. This is the fundamental assumption that underwrote Western dominance and its justifications, of which the British opium trade is particularly representative. It is this orientation that continues to underwrite notions of human exceptionalism and suprem

acy. To truly confront these consequences, and to be responsible to them, we must replace this way of thinking with another way.

I have a lot of sympathy for the argument, but let’s face it—it’s asking a lot. So I find myself looking closely at Ghosh’s language. If the poppy has historical agency, how does Ghosh demonstrate that agency? What is its character? And where else to look for the answers to these questions, other than his words?

At times Ghosh’s claims are couched with some diffidence: the non-human intelligence he senses at work here is a “feeling” that is “hard to ignore.” It indicates “a certain kind of vitality that manifests in innumerable ways, seen and unseen.” At other times, Ghosh is more straightforward. The poppy plant has “extraordinary powers,” and the fact that today’s polycrisis has forced us to reckon with them is “entirely positive.” Likewise, when describing particular actions taken during the period in question, Ghosh lands at various points on a kind of agency scale. Sometimes the poppy was merely “instrumental”; other times, it “colluded” with humans; still other times, it acted outright: expanding its circulation, creating addiction, defeating military powers, molding history. Of course, when he attributes direct actions to the poppy, he doesn’t mean the actions of any particular plant, the way we might discuss the actions of an individual human being, but the poppy as some Platonic universal, the poppy oversoul, perhaps.

“It would appear, then,” Ghosh writes in a summary sentence late in the book, “that the poppy, having been a major force in the making of modernity, will also be instrumental in its unmaking, a role that it will share with fossil fuels.” Here, the several ways Ghosh expresses the poppy’s agency are not precisely in harmony with each other. For instance, consider his use of the word “force.” Whether this metaphor has its origins in the structural violence of political power or the ancient science of physics, it is wildly overused as a way to explain causality. We all rely on the term “force,” almost constantly, but it betrays a fundamentally materialist orientation, precisely the orientation that Ghosh and other ecologically-mindful critics are striving to disrupt. Likewise, when he then refers to the poppy as an instrument—a tool—he continues to reinforce the modern conceptual system that perceives all non-human life as an exploitable resource.[i]

In the next clause, however, the poppy plays “a role,” a metaphor from the theater, where purpose is effected via analog symbolics. Unlike “force,” the plays-a-role metaphor supports Ghosh’s claim that the poppy possesses vitality and truly acts. But then that notion is immediately undermined once again: the poppy’s role, Ghosh writes, is “shared” by fossil fuels. Surely he doesn’t t claim the same intelligence and vitality for fossil fuels that he does for the poppy, given that the poppy—however universally he intends us to understand that term—is alive; whereas fossil fuels are definitively not alive but are the remains of life.

It is useful to subject Ghosh’s language to this sort of linguistic analysis? Ghosh himself admits that our biggest obstacle to challenging a materialist orientation is “the fact that the necessary vocabulary does not exist for thinking about history in a way that allows for the agency of non-human entities.” The contribution of scholars such as Ghosh is to chip away at that obstacle.

One of the ways Ghosh does this is to differentiate between what we might call human time and poppy time. The poppy “creates patterns,” Ghosh writes. It creates its own “temporalities.” It comes into and then “recede[s] from view.” The poppy’s agency exists within it’s own temporal dimension and is felt by humans systemically, in structures of class, in inequities of wealth and freedom, in geographies, in geopolitics. Societies struggle to manage systemic pathologies, just as individuals struggle to manage the consequences of addiction, patterns likewise sunk deeply into their own body’s natural history. Most of time these struggles, whether collective or individual, are in vain. We are not in control, as the 12-step programs say—our fates are in the hands of a “Power greater than ourselves.”

Power is another of those overused and problematic mechanistic metaphors. If the poppy acts and wields power, maybe it isn’t that its power is ‘greater,’ as in possessing more ‘force’ than human power does, but that it operates at a broader timescale than that easily perceived by humans. We might think of greater as older, wiser, more deeply integrated, more complexly related. In Smoke and Ashes, Ghosh shouts out to Robin Wall Kimmerer a time or two. Kimmerer’s project of honoring our “elders” in the plant world overlaps with Ghosh’s on animist grounds.

The attention Ghosh gives to differences in dimension and timescale likewise overlaps with the insights of the systems view. When articulating his ideas about “mind and nature,” the systems theorist Gregory Bateson emphasized the importance of understanding that in complex ecological systems, some informational loops are vast. An answer to a message eventually comes back around the loop, changing form along the way, but that circuit may take many human lifetimes to complete.

In making these connections—between his particular mode of environmental humanities and recent scholarship in indigenous thought and spirituality, and in turn, to the science of complex systems—Ghosh advances a merger of disparate intellectual projects, like circles closing in on each other in a Venn diagram. It’s the opposite of siloing. The shared space, which grows larger the more the circles converge, is fertile ground for the ecological imagination.

It is ground, too, for the moral advocacy that the ecological imagination implies. “Only by recognizing the power and intelligence of the opium poppy can we make peace with it,” Ghosh writes. Recognizing the poppy’s power and intelligence, or, more broadly, the power and intelligence of non-human life, “would mean parting company with many ideas that have long been dominant, such as the notion that the earth is inert and humans are the only agents of history.” Those ideas and notions have been described by a host of thinkers as Cartesian, Baconian, as materialist-utilitarian, as modern. They “created a system in which indifference to human suffering was not just accepted by ruling elites but was justified and promoted by a plethora of false teleologies and deceptive theories.” That indifference is the same indifference that “makes it possible today for the wealthy and powerful to be suicidally indifferent to the prospect of a global catastrophe.”

What Ghosh and others advocate for, then, is a fundamental reimagining of perception. This advocacy is a moral one because it involves matters that cannot be solved technologically but that must be adjudicated with a moral conscience. Whether we are indifferent to or sensitive to the suffering of others, and whether we are indifferent to or sensitive to “the prospect of global catastrophe” may hinge on the same thing: whether we attribute intelligence and agency to life in the non-human world.

This essay appeared on the Society for US Intellectual History blog.

[i] In their 1980 book, Metaphors We Live By, George Lakoff and Mark Johnson define ‘conceptual system’ as the system of concepts that “structure what we perceive, how we get around in the world, and how we relate to other people. Our conceptual system thus plays a central role in defining our everyday realities.” Conceptual system is therefore essentially synonymous with many other terms such as ‘fundamental orientation,’ ‘mindset,’ ‘worldview,’ ‘mental maps,’ ‘frames of reference,’ etc.

Favorite Reads of 2023

Happy New Year! Below are my favorite reads from last year, all highly recommended.

Our Migrant Souls: A Meditation on Race and the Meanings and Myths of “Latino” by Héctor Tobar. Born in 1963 in LA to parents newly arrived from Guatemala, Tobar has written journalism, novels, and works of non-fiction. My first exposure to his precise, insightful prose was an essay titled, “The Assassin Next Door,” published in the New Yorker several years ago. That piece combined memoir with national history to demonstrate how racist hatred and transracial solidarity are nurtured within the same American spaces. In Our Migrant Souls, Tobar adds to this combination what he’s learned from the lives of his Latino students as an instructor of writing and literature. Writing about the Latino experience is typified by tales of hardship, discrimination, and family dysfunction. In contrast, Tobar emphasizes the courage of the immigrant, and how their initial boldness—that decision to migrate, to court danger and loss—becomes the foundational story of so many American families.

Poverty, by America by Matthew Desmond. Whether I’m reading history or sociology, natural science, memoir, or even fiction, I’m not used to having my conscience stung so directly. Desmond’s analysis, in general terms, was far from unfamiliar. But his delivery of it spotlights the role of complacency and makes the whole question of the persistence of poverty a moral question. I took this up in detail in my last post on this blog. Desmond believes in the efficacy of policy, most especially when it has widespread political support and is shaped to be inclusive in its benefits. But for Desmond, the crucial question about poverty is who benefits from it, to which he answers “the rest of us.”

King: A Life by Jonathan Eig. Turns out I was wrong to think I didn’t need to read another Martin Luther King, Jr. biography. This one, by humanizing him, serves as a corrective in an era of warped MLK iconography. Eig stresses King’s precarious mental health under conditions of unimaginable stress and fear of attack, the FBI hounding he received, driven by J. Edgar Hoover’s deep, racial animus. Eig also foregrounds the perspective and contribution of his wife and movement partner, Coretta King. One gets a sense of the shortness of King’s life, his youth, his uncompromising understanding of the leadership role he’d accepted, and the decisive quality of his faith in a personal God. The result is a moving read and, for me, an even deeper admiration.

Crook Manifesto by Coleson Whitehead. Whitehead has tried his hand and succeeded in several genres of fiction. He reaches near-perfection with Crook Manifesto, the second book in his Ray Carney crime series set in 1960s and 70s Harlem. Carney is a neighborhood furniture store owner with a foot on each side of the law. On one side is his legit life, his business, his wife and young children, his wish for his family to prosper and rise. On the other side is his “bent” life, the now-and-then fencing and shady acquaintance that are necessary to keep his aboveboard life afloat. That the two sides coexist in contradiction makes for great suspense, cultural history, specificity of language, time and place, and sharp commentary on the conditions of Black life in America. The plot is set in motion by Carney’s desire to get his teenage daughter tickets to the Jackson 5 concert. Things just get better from there.

Lessons by Ian McEwan. I re-read this 2022 book in 2023. It’s McEwan’s seventeenth novel, and again one of the great English prose stylists takes up one of his enduring themes: the steep price an artist pays for their devotion, whether or not it’s morally justified. Here, in a book that rivals Atonement as the author’s masterpiece, McEwan delivers a corollary, which I found welcome, especially compared to the colder conclusions he comes to in some of his other books. A half decade or so younger than Biden, Dylan, the Beatles, and the Stones, McEwan has reached an age from which he can contemplate with authority a life as a whole, its ups and downs, its feasts and famines, its twisting trajectories. To American scholars of the Cold War and of the unexpected politics and economics of its aftermath, the book grants the experience of these years from a European perspective—closer to the action in several respects.

Trust by Hernan Diaz. This ingeniously constructed work of metafiction was published in 2022 and this year was awarded the Pulitzer Prize. With it and its predecessor, In the Distance (2017), another terrific but lesser-known work of historical fiction, Diaz emerges as a major writer. The book demonstrates the author’s deep research in 1920s Wall Street tradecraft, his command of magnate discourse, his familiarity with period texts, and his deep appreciation of Borges. We are again living in an age of unchecked corporate arrogance and power. Dangers loom, and when our bacon is saved, it’s often due to female agency against the odds. It’s a timely, resonant book.

Quantum Criminals: Ramblers, Wild Gamblers, and Other Sole Survivors from the Songs of Steely Dan by Alex Pappademas with illustrations by Joan LeMay. This is the outlier on the list, mostly because its topic, the rock group Steely Dan, is likely of limited interest. For both 1970s punk and 1990s grunge rockers, Steely Dan epitomized the contemptible sound of slick, complacent professionalism. Now the group has been discovered and celebrated by a new generation, and Pappademas, one of these new aficionados, explains why. First, digital recording technologies have made slickness less a privilege than a choice. Second, and more importantly, the group’s “blue ribbon misanthropy” was prescient. “Our fast-warming world,” Pappademas writes, “is more Steely Dannish than it’s ever been.” Witty, articulate, full of tasty references, Quantum Criminals is that rare work of criticism that sustains its verve to book length.

A version of this post appeared in the Society for US Intellectual History blog.

Provocation and Hope in Matthew Desmond’s Poverty, By America

It is the nature of contemporary life, I suppose, that events less than a year old seem to have happened long ago. It was only last March that I read Matthew Desmond’s Poverty, By America. That book should have dominated public conversation. It should been hashed over in every corner of the media and fast-tracked as a Netflix series. A friend read it, and we talked about it for a week or so. But every few days, a new emergency arrives and covers over the one that came before it. Did Desmond’s book get enough play? It doesn’t feel like it.

That might make sense had the book been an indigestible doorstopper, but Poverty, By America is a quick read, less than 200 pages minus the notes, written in swiftly-paced prose, and laser-focused on its argument: that poverty in our nation is the result of systemic exploitation in the sectors of labor, housing, and finance; that, in other words, our economy is structured to make—and keep—a large segment of its population poor.

Nothing new, some might say. To explain the persistence of poverty, liberals and leftists typically speak in terms of systems. Oppression and exploitation inhabit and are reproduced within institutional structures. The right, in contrast, focuses on individual character. Hard work and self-discipline, the ability to defer gratification, wise life decisions, and piety are what make the difference between prospering and being poor. Moving further rightward along this spectrum, defects in character are associated with some racial essence, and racist ideas are mobilized by racist power.

Without arguing in an explicitly partisan manner, Desmond offers plenty of empirical evidence to support progressive modes of analysis and examples of liberal policies that have proven to be effective toward leveling the economic playing field. He also offers evidence that demonstrates the failure of right-wing, character-based policies. Yet he declines to rest in structural explanations. “At the end of the day,” Desmond asks, “aren’t ‘systemic’ problems—systemic racism, poverty, misogyny—made up of untold numbers of individual decisions motivated by real or imagined self-interest?” (40-42).

I frowned at the question, reminded of Margaret Thatcher saying there is no such thing as society, reminded of politicians pontificating about ‘colorblindness’ and defining racism as entirely a matter of the individual human heart. But Desmond’s point is that both structural and character-based explanations can be ways to evade responsibility. “Tens of millions of Americans do not end up poor by a mistake of history or personal conduct,” he writes. “Poverty persists because some wish and will it to” (40).

Poverty persists, in other words, because there are beneficiaries, and those beneficiaries aren’t only the super, crazy rich, not only the homegrown oligarchs so chillingly satirized in the HBO series, Succession. Those beneficiaries are any of us whose free bank accounts, for instance, are funded by the overdraft penalties that the poor regularly pay, any of us whose home values have skyrocketed due to the manufactured scarcity of affordable housing or whose mortgage payments are offset by the Mortgage Interest Deduction. Those beneficiaries are any of us invested in the stock market, even through their employer retirement investments. It’s one thing to say that the economy is structured to make a segment of the population poor. It’s a step further to point out how their poverty funds the prosperity of the other segment.

If this isn’t troubling enough, Desmond draws an analogy between the persistence of poverty today and the persistence, in earlier times, of chattel slavery. The free benefited from the exploitation of the enslaved, and not only the southern oligarchs, the slaveholders, the slave traders, not only white Americans in the South, but all free Americans, as groups, as families, and as individuals. Desmond calls for Americans to become “poverty abolitionists,” and as the nineteenth-century anti-slavery abolitionists did, to take a stand, join the movement, disavow the benefits, and act to bring poverty to an end.

Here again I shifted in my chair. During those days of the US History course that I teach, when we’re covering the antebellum period, the abolitionist movement, and “the Crisis of the 1850s,” the question has crossed my mind more than once: Would you have been an abolitionist back then?

I won’t belabor the logical problems this sort of inquiry involves except to say that we are products of our historical moment. There’s no going back in time and being the same person you are now. Yet the question keeps returning. It’s trying to get at something. Abolitionists were those willing to be vilified and put in danger of attack or exile. To be an abolitionist was to be annoying, a troublemaker, an agitator of the social peace. It was to be willing to put one’s future at stake. So when I ask myself, would you have been an abolitionist then, what I’m really asking is, are you willing to be the equivalent of one today?

Some of us, when an idea disturbs our peace of mind, follow the homeopathic school and seek out more of the same. I went back and read Desmond’s previous book, Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City, (winner of the Pulitzer Prize in 2017) and then a more recent book by Tracy Kidder called Rough Sleepers, about the homeless in greater Boston.

Kidder’s hero is a doctor named Jim O’Connell. O’Connell was a gifted student of philosophy who came to medicine late in life. Overwhelmed by the great human problems, he finds peace in service to the poor. He treats their diseases, tends to their wounds, loans them money. He washes their feet in a kind of pride-purging ritual. One of the ongoing conflicts of the book is that although O’Connell helps individuals, his work does little to nothing to solve the general problem. When from time to time the truth of this discourages him, he remembers his mentor, Barbara McGuinness, a nun who ran a city clinic. It wasn’t uncommon for a new volunteer at the clinic to raise exactly the question that haunted O’Connell: What can we do to fix the problem itself?

McGuiness had little patience for the question. The important thing, she’d say, was to “do the best we can right now and take care of these folks.” O’Connell didn’t love the answer, but he accepted it. “This is what we do while we’re waiting for the world to change.”

Desmond shows a similar impatience with abstractions now and then in Poverty, By America. For instance: Is abortion immoral? What are the limits of bodily autonomy? When does life begin? These questions can never be resolved, Desmond states. What he knows for certain—what, in other words, sociology shows—is that when access to abortion is restricted, the number of women suffering poverty increases, and women already suffering poverty, suffer more. Evidence from sociology also supports the effectiveness of anti-poverty programs, especially those that put money directly into poor people’s pockets. Poor people tend to use that money to leverage opportunities and practices that serve to buffer against poverty’s ever-narrowing constraints.

Desmond cites, for instance, those arrangements that aided workers during the pandemic—tax breaks, direct checks from the government, protections against eviction, suspended loan payments, and so on—that not only worked to help sustain life under pandemic restrictions but that resulted in a significant reduction in poverty. Desmond has policy ideas that could be put into place immediately: Beef up the enforcement arm of the IRS so that the wealthiest tax cheats pay their fair share. Get rid of those tax policies, such as the Mortgage Interest Deduction, that don’t reduce poverty so much as they subsidize wealth. “Tear down the walls” that allow resources to be made scarce and that in turn allow the poor to be corralled into spaces that facilitate their exploitation.

These are “liberal” ideas, by any conventional understanding of the word. For those who take a more radical stance, these policy ideas are insufficient. For these folks, many of them young—the age of my children, of my students, with their whole (none-too-promising) futures ahead of them—the situation is too dire, too urgent for liberal tinkering. They might also point out how Desmond has nothing to say about the climate emergency. Desmond’s policy recommendations may indeed result in a ticking down of the poverty index. But will they have any effect on the collapse trajectory?

For some who think this way, the change space is in fundamental orientation, worldview, metaphysics, the social imaginary, what-have-you. Desmond is evenhanded here, too. Along with his policy suggestions, he includes passages that speak to the social imaginary. He quotes, for instance, from Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd: “The history of the world, my sweet, is who gets eaten and who gets to eat.” This predatory, hyper-competitive model continues to dominate the center of social reality, despite a constant stream of criticism. Desmond astutely points out how we condemn such arrangements when they occurred in the past, as with slavery, but in the present, tend to let them slide. Why? Desmond speculates that we are “captivated by a heroic narrative of progress” (43). The very fact that these critiques are so old and familiar makes me doubt the very possibility of change at this level of abstraction.

On this matter, Desmond quotes James Baldwin:

Any real change implies the breakup of the world as one has always known it, the loss of all that gave one an identity, the end of safety. And at such a moment, unable to see and not daring to imagine what the future will now bring forth, one clings to what one knew, or thought one knew; to what one possessed or dreamed that one possessed.

The quote comes from Baldwin’s 1956 essay, “Faulkner and Segregation.” It’s another reminder of the correspondence between American poverty and the legacy of enslavement. Desmond hastens to add that giving up our identity as modern people also means giving up the baggage that goes along with it, the shame of living well in a society where so many struggle to procure the basic necessities. It means giving up “the loneliness and empty materialism” of contemporary life (176-77).

To be clear, Desmond believes Americans can abolish poverty but “only when a mass movement demands it so” (184). He sees promise in present-day labor movements and movements for housing justice. He gives People’s Action and William Barber’s Poor People’s Campaign each a shout-out. He quotes Deepak Bhargava, former president and executive director of the Center for Community Change. “Get into relationship,” Bhargarva advises. “Find some way in your life to be in relationship with working class and poor people” (185-88)—not the relationship of a person of means giving charity to someone in need, but a relationship of equals working together in a political cause.

“Would you have been an abolitionist back then?” That question I asked myself in class was always fleeting, as if something were keeping me away, some avoidance of disappointment in myself, perhaps, and on the other side of that, a crush of hopelessness and futility. If it is indeed possible to make change in abstract imaginaries, there’s a force field, a strong one, warding it off. Partisan polarization may be a component of the force field, or as Desmond puts it, “just another scarcity diversion, just another way to narrow our vision so that an emancipated future remains outside our field of view” (188). He doesn’t believe that the issue of economic injustice is a partisan one. He believes it’s a cause everyone can get behind.

This essay was published at the Society for US Intellectual History blog.

Richardson and Woodard: It Tracks

In Heather Cox Richardson’s new book, Democracy Awakening, US history turns on conflicting interpretations of the Declaration of Independence and its claim that “all men are created equal.” One interpretation is broad and expansive, the other narrow and strained. The broad one figures the word “men” generically to include both men and women. It understands the word “equal” expansively: equal in access to rights, equal under the law, equally free to participate in civic life and to have a say in governance at all levels. The opposing interpretation ties itself in knots to narrow and qualify those “self-evident” words. Interpreted broadly, the Declaration refutes the old feudal order, its authoritarian structure, its hierarchy of tradition and castes. The narrow interpretation seeks to rescue its “hierarchical vision,” as Richardson puts it, and to defend it as natural or as divinely sanctioned. The broad interpretation is more popular and persuasive than the narrow one, and when the rationales and legal theories of the advocates for the narrow interpretation fail to win over the majority, they resort to lying, cheating, violence, and terror.

Am I oversimplifying the argument? Maybe. It’s certainly a boiled-down version of US History. But it tracks.

It tracks, for instance, with the way Colin Woodard sees US History. Woodard’s argument, presented most plainly in his much-read 2011 book American Nations, is that US history is best understood as the history of conflict between distinct regional cultures in North America. Two of these, which Woodard calls “Yankeedom” and “Deep South,” have been in an ongoing struggle over control of the federal government from the start. Yankeedom has its roots in Puritan Massachusetts, and although its zeal to impose a one-size-fits-all program for the greater good may annoy outsiders, its utopian spark supports the more expansive view of American equality. The Deep South is rooted in the sugar plantations of Barbados, transplanted to the Carolinas in the second half of the seventeenth century. It has always held and defended the hierarchical vision, the narrower interpretation of the Declaration.

When I first read American Nations, I had been primed for its argument by David Hackett Fischer’s Albion’s Seed. That book, which I came across in my father’s library, helped me locate myself and my own upbringing and ancestry. Since the topic of “where we came from” never came up in family conversation, Fischer’s study made sense of what had been hazy before. American Nations, aimed at an audience outside the academe, is a more assessable book than Albion’s Seed. I found its argument enormously persuasive, so much so that alarm bells went off.

The part of the argument that bothered me was the way it generalizes vast groups of people, assigns to them lifeways and bodies of belief, and then invites the passing of judgment upon them. Yankeedom folks are scolding and inflexible, Tidewater folks haughty and classist, New Amsterdamers tolerant but mercenary, Borderlanders clannish and defensive, and so on. On the one hand, this seems like plain stereotyping. On the other, didn’t South Carolina’s political leadership consistently take the lead in nullification, secession, segregation? Isn’t the “hierarchical vision” and narrow interpretation that Richardson identifies as the traditional enemy of American democracy plainly evident in the literature of the Deep South, from Alexander’s cornerstone speech to Thomas Dixon’s The Clansmen to Woodrow Wilson’s books of history to Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind? And, only to be a little facetious, aren’t Richardson and Woodard both popular historians with home bases in Maine?

No argument is possible without generalization. Where you draw the line makes the difference and how much you admit to the ultimate falseness of all lines. Yet the question persists, why do people hold some beliefs and not other beliefs? Let me put it in a way that better aligns with Richardson’s book. If the central conflict among Americans is the rejection or the defense of a “hierarchical vision,” whether it manifests itself in the way one interprets the Declaration of Independence or in the way one feels about Donald Trump, what is the essential source of the difference? Rationality? Pecuniary interest? Some felt connection to a higher telos? Or is it simply because of the way you were raised?

George Lakoff’s thesis comes to mind, that the distinction lies in whether one’s family adhered to the model of “strict father” or “nurturant parent.” The former winds up friendlier to a politics of authoritarian hierarchy, the latter to one of empathy, tolerance, and a flatter distribution of power and resources. Whereas Lakoff’s evidence comes from the neuroscience laboratory, I tend to prefer Woodard’s, which comes not only from the analysis of political and literary texts, but from voter rolls and dialect regions. Woodard, leaning heavily on Wilbur Zelinsky’s 1973 Doctrine of First Effective Settlement, would argue that beliefs have their origins in historical experience, migration and the founding of a socio-economic community. The belief system associated with that founding is then reproduced generation after generation by cultural means. For Woodard, therefore, place has a stronger influence than parental style. Where you grow up becomes determinative in most cases, although heterodoxy is possible “with great effort” made “later in life.” One assumes that education is crucial to that effort.

Heterodoxy in regard to upbringing has been a theme in my own life, as has education. I’ve read widely and systematically and received fairly rigorous training in critical thinking. Of course, this is also what sets off the alarm bells when I find myself highly persuaded. Ever since I first read Woodard’s American Nations—and recently, his brilliant Union: The Struggle to Forge the Story of United States Nationhood (2020)—I’ve been seeking out opposing arguments, insights to dampen enthusiasm. I’m still looking.

ENACTING ECOLOGICAL AESTHETICS

On October 31 (18.00-19.15 CET), Anthony Chaney will be speaking about his research to an international group of designers and architects for a project called Enacting Ecological Aesthetics. https://www.enactingecologicalaesthetics.com/anthony-chaney-in-conversation-with-dulmini-perera/

King, A Life and Blood Meridian: Reading Under the Heat Dome

By September 1st in Dallas, Texas, we’d been living under a heat dome for two and half months. The days during which it was actually pleasant to be outside could be counted on the fingers of one hand. I’m sure I wasn’t the only one who kept thinking about packing up and moving away, as if we truly enjoyed that sort of flexibility. Besides, where would we go? The summer has been brutal, that’s true, but that brutality is preferable to one’s house burning down in a wildfire or flooding in some unprecedented rain event. No one is safe. No one is well-positioned. The climate emergency is too enormous.

Yet we can meet it, experts tell us. The tools and know-how exist. All we lack is the political will. Okay, all right, but that’s not a lot of comfort when what’s happening today in the environmental realm is only slightly more scary than what’s happening today in the political.

In short, I don’t think one has to be living under a heat dome all summer to experience multiple varieties of anxiety, climate grief, extreme mood swings, and the back-and-forth between brave efforts to generate hope and the far more frequent lapses into dread and despair.

The ups and downs of it all came home to me in a personal way when I happened to notice a couple of the books I’d been reading over the summer, one stacked on top of the other, on the end table next to my living room chair: Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy (1985) and this year’s King: A Life by Jonathan Eig. The juxtaposition was commentary.

The McCarthy I read decades ago; why on earth would I pick it up again? Partly it was to commemorate the author’s recent death, but mainly it was due to his two interconnected final novels published late last year. The first of the two, The Passenger, which I read almost the moment it became available, was so disappointing that I needed to go back and see if the alleged masterpiece of decades ago actually held up. So much has changed since the 1980s. So much I took as foundational, as canonical, has required re-evaluation, especially concerning matters of geopolitics, gender, and race. The world has changed. I’ve changed. Maybe the books changed, too.

So I’ve been giving Blood Meridian a slow, patient read, a section or so per day. The verdict? I don’t know, maybe my capacity for horrific input has increased, or maybe it’s just life under the heat dome, but yes, it holds up. It’s even better than I remember it. I’m in awe of the language and the achievement of imagination, even if it’s a question of whether that achievement is ultimately defensible, given that what has been imagined is human depravity in all its depth and detail. The roving band of scalp-hunters ride into the city of Chihuahua, “to a hero’s welcome,” newly arrived from their latest massacre. They strip naked and settle into the public baths, the waters of which rise around them, transformed into “a thin gruel of blood and filth.” Such examples of virtuoso granularity can be found on pretty much every page.

There are also gestures here and there that I wouldn’t have picked up on when I read the book the first time simply because they speak to issues that weren’t on my radar. In the very first chapter, for instance, setting the stage for the whole book, “the kid” is pushed westward by fate into the contested borderlands where “not again in all the world’s turnings will there be terrains so wild and barbarous to try whether the stuff of creation may be shaped to man’s will or whether his own heart is not another kind of clay.”

May the stuff of creation be shaped to “man’s will”? Yes, it may, which is why we’re calling that stuff today the Anthropocene, and why the planet is heating so rapidly. But what does this say about “man’s will”? Were heat domes, wildfires, floods, climate migrations, and the sixth extinction the shaping that will intended?

We must cease the burning of fossil fuels, but one doubts whether habits so deeply sunk can be broken. It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than it is the end of our dependence on fossil fuels (to slightly tweak a well-known phrase). I’m not much persuaded by new programs for shaping “the stuff of creation.” By reason or by temperament, I’m more drawn toward those that advocate for reshaping what McCarthy refers to as man’s “own heart,” that “another kind of clay.”

But at this point, we can’t continue to use such language as “man” and “his own heart” in the same, once-routine way that McCarthy does. The “man” responsible for the Anthropocene is not universal man but the man of the modern West and his particular way of organizing perception, the man we associate with Western imperialism and the industrial and technological revolutions. That man tended to perceive the New World the same way McCarthy does: as terrain empty of history and therefore a kind of laboratory in which such things as progress and “man’s will” might be tested.

Rather, we think in terms of particular societies with particular histories and ways of seeing the world. We examine bedrock assumptions about nature, human nature and society, and how these assumptions expand or limit what is imagined to be possible. Rather than some universalized human heart, these particular assumptions and habits of perception become the locale of change. Many terms have been used to refer to this change space: worldviews, mindsets, orientations, paradigms. The technology-minded might favor the term “programming.” A term newer to my experience is “imaginary” or “social imaginary.” At times, people have spoken about that space as the realm of values, as in the call for “a radical revolution of values.” This was the change that Martin Luther King, Jr. called for in his April 1967 speech in which he connected the civil rights struggle to economic exploitation and the American military intervention in Vietnam.

If reading McCarthy put me in awe of his artistry, but also kindled feelings of despair over human prospects (to put it mildly), reading Jonathan Eig’s new biography put me in awe of King’s faith and courage, and moved me in ways that, at least in moments, relieved the despair. As expected of a new life of such a significant historical figure, Eig makes use of newly available sources of evidence and emphasizes what they reveal. In this case, much new material came from FBI records, and Eig provides a clearer understanding of J. Edgar Hoover’s racist hatred for King, how personally affronted he was by King’s sexual indiscretions, and how relentless he was in using institutional power to thwart King’s efforts and the movement in general.

What does it mean to be made a target by the very powers assigned to protect you? What are the consequences of that? (The election worker Ruby Freeman, also of Atlanta, has recently asked the same question.) Years ago, I read Taylor Branch’s “America in the King Years” series, but I don’t remember feeling such appreciation for the psychological battering King accepted from the moment he stepped forward to become the voice and face of what became the Civil Rights Movement. That battering included, from the beginning, the fear of imminent assassination.

What sustained King? Partly, Eig tells us, it was the faith that he had been called by God to serve. Early on, King claimed that this faith allowed him to make peace with death. Eig’s narrative shows how uneasy this peace actually was. King paid an enormous toll in damage to his physical and mental health and was regularly hospitalized for episodes of severe fatigue and depression.

King was sustained, too, by the belief, also grounded in his Christian faith, that personal suffering was a necessary step toward societal redemption. Eig comes back to this point again and again. “King was a product of the Black church,” he writes. “He learned the values of love and sacrifice and humility from the church, and he learned to live those values. His visions served to intensify what was already an intense personal relationship with Jesus Christ. One part of that relationship was his understanding that Christian social action, suffering, and martyrdom were connected.”

I don’t relate to the doctrinal particulars of King’s faith, but I’m intrigued by the dynamic that faith proposes. I’m struck by how it’s aimed at the very change space of the social imaginary. I mean, if anything runs more counter to the imaginary of competitive self-interest and material growth that predominates in American society and that frames our behaviors collectively and individually, it’s the voluntary acceptance of suffering in the interest of societal redemption. And for that matter, is there any better scenario, not for countering that imaginary, but for reinforcing it, for taking it to its logical conclusion than the one Cormac McCarthy describes in Blood Meridian page after page after page?

This essay was published earlier this month at the Society of US Intellectual History Blog

Reciprocity and the Exchange of Blows

It’s Christmas Day and King Arthur’s knights are gathered at the round table, celebrating with the king and queen. The Green Knight, a kind of giant tree-man, rides in on horseback, interrupts the party, and challenges anyone present to a game. Here are the rules: The challenger will be allowed to deliver a blow that the Green Knight will receive without resisting. But first the challenger must agree to seek out the Green Knight in one year’s time and receive without resisting the same blow from him.

This is the set-up to the epic poem, “Sir Gaiwan and the Green Knight,” circa 1300, which I read in a couple of translations after seeing the recent film adaptation, The Green Knight. I’d never read the poem before, but the more I thought about its opening scene, the more I thought: how weirdly precise … and how familiar.

My brother and I, when we were kids, would take turns punching each other in the stomach. I recall, too, a scene from a comedy about insanely competitive college ballplayers, in which teammates take turns thumping each other’s knuckles with a flicked middle finger until the skin over their fists is flaming and their eyes are watering with pain. This is a boys’ thing; this speaks to what it supposedly means to be manly—brave, tough, strong.

Still, the round table knights, big burly fighting men, hesitate to take the Green Knight up on his proposal. The possibility of winning a contest of this sort would depend on one’s belief that his capacity to dish out and take punishment outweighs that of his opponent, a giant who resembles a tree. Who would accept such a challenge? Let me rephrase that. What kind of stupid would a person have to be to take part in a game like that? In answer, I’ll simply say that my brother was two years older than I was, a lot stronger, and although, in our stomach-punching game, I never made it past the first round, neither did I ever refuse to play, and in fact, playing was, as often as not, something I myself initiated.

I may have been acting on an impulse that reaches far back into mythic time. It turns out that “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight” is not the only ancient tale that involves a similar challenge. Scholars have called it “the exchange game.”

Gawain, Arthur’s nephew, seated by his side, steps up and accepts the challenge. Making the most of his first-turn advantage, he takes a sword and beheads the Green Knight in a single stroke. To the surprise and horror of everyone in the hall, the Green Knight stands, picks his head up off the ground, reminds Gawain of the bargain, and rides away with his head in his arms.

More commonly in Arthurian studies, this particular version of the exchange game is referred to as the “Beheading Game.”

In my last post, I wrote about Robin Wall Kimmerer’s book, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants and its concept of reciprocity: the biosocial bond between human and non-human life created by the giving and receiving of gifts and the gratitude and obligation it engenders. I wrote, too, about Kimmerer’s project of restoring healthy relations between human and non-human nature as re-story-ation. “Stories,” Kimmerer writes,

are among our most potent tools for restoring the land as well as our relationship to land. We need to unearth the old stories that live in a place and begin to create new ones, for we are storymakers, not just storytellers. All stories are connected, new ones woven from the threads of the old” (341).

Back in the 1980s, physicist and cosmologist Brian Swimme called on artists, poets, mystics, and nature lovers to tell a “Cosmic Creation Story” that connected the big bang, the Gaian emergence of atmosphere and soil, cell symbiosis, the music of Mozart and other works of human genius in a continuous line of creative adventure. More recently, in his 2021 book The Nutmeg’s Curse, Amitav Ghosh argues that lasting solutions to our various crises must be rooted in “a common idiom and a shared story—a narrative of humility in which humans acknowledge their mutual dependence not just on each other, but on ‘all our relatives'” (242). These are only two examples of many who believe, as Kimmerer does, that new and repurposed stories are crucial to disrupting our current trajectory of collapse and to building a constituency for transformation.

Kimmerer’s background gives her access to a storehouse of Indigenous myth to draw on and interpret for present times, but she warns against the “wholesale appropriation” of Indigenous stories, advising that “an immigrant culture must write its own new stories of relationship to place” (344). On the other hand, I seem to remember at some point in the book—I couldn’t find the location in my notes, and, unfortunately, Braiding Sweetgrass includes no index—Kimmerer reminds her readers that all peoples have a past to draw on that is indigenous to somewhere. The implication is that even the immigrant community she is referring to must have some claim—however attenuated, however muddied by subsequent adjustments—to pre-modern myth and to a time when human groups lived more reciprocally with, as Ghosh puts it, ‘all our relatives.'”

It was with all this in mind that I saw David Lowery’s 2021 film, The Green Knight, much lauded by critics but not I think very widely seen. A few of those critics remarked on the film’s ambiguousness, that two viewers might walk away with very different opinions as to the film’s topic and message. Be that as it may, I’ll continue with the story.

A year passes, and to make good on his promise, Gawain journeys to find the Green Knight. As Christmas Day approaches, he comes upon a castle where he’s welcomed by a Lord and Lady. The Lord encourages Gawain to stay a few days and soon proposes a playful exchange. The Lord will hunt during the day and bring back whatever he kills as a gift to Gawain. In return, Gawain will stay in the castle with the Lady and her maids and will give to the Lord whatever good things he receives there. Gawain doesn’t quite understand the point of the proposition, but he agrees.

The hunt, the castle—these episodes make up the bulk of the poem. As do many literary works from an oral age, they play to a wide audience. The descriptions of the hunt are vivid and exciting. They are all about danger, daring, and action. The castle passages are of a different order. The Lady is intent on seducing Gawain. Will he be virtuous, rebuff—and perhaps insult—the Lady? Or, given the likeliness that he will soon be beheaded by the Green Knight, will he take a pleasure offered while he can?

These aren’t the only dilemmas. If Gawain does accept what the Lady is offering, will he make good on the agreement with the Lord and return the same to him? In these castle passages, we have a moral dilemma, we have the ancient question, how should one behave knowing that death is unavoidable and that one’s time on earth may be cut short at any moment? We also have the components of farce.

The director David Lowery makes a few wise adjustments and additions to this basic story. Foremost, he makes Gawain a young man, not yet a knight, a lazy youth who has skated along on his privilege. His story, therefore, becomes a bildungsroman, his journey about the formation of character. That gives the story an arc less discernable in the poem. Without losing the framework, Lowery also keeps a stricter control of tone, emphasizing the existential qualities and deemphasizing the low comedy.

But let’s think about the story in Kimmerer’s terms. First, it’s a tale from the immigrants’ indigenous tradition, reaching back to the early medieval period, with components—particularly, the exchange game motif—that surely go even further into the past. Second, the two games Gawain is involved in—one with the Green Knight, the other with the Lord—are inverted versions of each other, each dramatizing the matter of reciprocity. Both the poem and film render the Golden Rule in ways that transform it from a platitude into a problem of giving and receiving. As a human being in the world, within a household, within a wider ecology: Are you willing to take as you give? Are you willing to give as you take? Are you willing, in other words, to truly engage with others in a reciprocal relationship?

Braiding Sweetgrass is a work of cultural ecology, and my discussion of the film is in the same spirit of critique. What I mean is, Kimmerer’s survey of our “broken” ecology, our bad faith relationships within the web of life, aims mostly at the realm of culture—questions of how stories and ideas shape our account of ourselves as living beings within a living world. Traditionally, cultural critiques have themselves been criticized as shallow, facile, romantic, quietist, anti-modern, and, for these reasons and others, too easily recruited by the forces of political reaction. Whatever the original sources for the Green Knight story may be, the poem which has come down to us certainly bears the marks of a patriarchal, Christian society. On the other hand, the nature of myths is that they can contain the materials for their own subversion. This paragraph, in other words, means to raise a number of new questions. But this post is long already, so for now at least, I’ll leave it here.

A version of this essay first appeared in Society for US Intellectual History.

NOTES:

Swimme, Brian. “The Cosmic Creation Story” in The Reenchantment of Science, ed. By David Ray Griffin, (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 1988), 47-56.

An Alchemy of Giving: Reciprocity in Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass

At some point, intellectual historians will have to reckon with the phenomenal success of Robin Wall Kimmerer’s book, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. When they do, they may place it among the most important works of its kind, up there with Walden, say, or Silent Spring. Now is probably not the time. First published in 2013, it is at this writing number three on the New York Times bestseller list of non-fiction books in paperback, a list it has appeared on now for 131 weeks.

What accounts for the book’s success? Certainly, a genre exists for lyrical nature writing. But it appears that Braiding Sweetgrass has crossed over to a wider audience. In the midst of this era of multiplying, accelerating crises, there is something emotionally stabilizing about Kimmerer’s book, and I think that can be attributed to her central concept: reciprocity.

Kimmerer is a professor of botany, trained in universities and mainstream science. But her concept of reciprocity comes from her background as a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation and her training in Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK). In the creation story with which she begins the book, Skywoman falls from above in a beam of light. The creatures in the darkness catch her, care for her, make for her a home of mud, and she reciprocates with the bundle of seeds she carries in her hand. In this way the earth was made, “not by Skywoman alone, but from the alchemy of all the animals’ gifts coupled with her deep gratitude” (4). An alchemy of reciprocal gifting, in other words—you receive a gift, you’re grateful, and you give a gift, and that creates a bond. Kimmerer later gives this a more systems science description: new arrangements are created, old ones transformed, by a joining of “obligate symbiosis” (343).

Indeed, Kimmerer is braiding together a kind of intellectual symbiosis between TEK and a systems science-informed biology that pushes back against conceptions that have long persisted in popular thinking about life and how it works. We are used to the idea of human life as essentially a struggle against a hostile environment. We are used to the idea that what is exceptional about human beings is that they are inherently ‘out of balance’ with their environment, that some sort of parasitic selfishness is the essence of human nature. In contrast to this, Kimmerer encourages readers to imagine what “beneficial relations” between humans and their environment “might look like” (6). What she describes is less a struggle than a kind of letting go. “A gift comes to you,” Kimmerer writes,

through no action of your own, free, having moved toward you without your beckoning. It is not a reward; you cannot earn it, or call it to you, or even deserve it. And yet it appears. Your only role is to be open-eyed and present. (23-24)

This passage comes from a chapter that draws on Lewis Hyde’s 1979 book, The Gift: Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property. But I’ve heard the theological concept of grace similarly described. Certainly, the familiar transfer of religious ideas to ecological thinking is present in Kimmerer’s language. From the Indigenous perspective, of course, there was never a division between the two. Her TEK is as spiritual as it is empirical.

My father-in-law, wholly secular, a mathematician, used to say that for him a walk in the forest was a sufficient substitute for church. That’s not an unusual sentiment. Familiar too are claims, expressed by many, that they ‘love’ nature, that they love the natural world. The idea of reciprocity provides for the rarer situation; it provides a way to conceive of nature as, in Kimmerer’s words, receiving people’s love and loving people back (122). If you’re going to think of yourself in a reciprocal relationship with an ecosystem in the way Kimmerer means it, you’re going to have to allow yourself to think about ecosystems as having spirits—or minds—of their own. You’re going to have to partake in some animism.

That’s asking a lot. For many secularists and religious folk alike, that’s taking a step onto uncomfortable ground. “How, in our modern world,” Kimmerer asks, “can we find our way to understand the earth as a gift again, to make our relations with the world sacred again?” (31).

She answers by telling stories. Some are personal stories about her experiences with her children in the garden or with her students in the woods. Others, like the story of Skywoman, are Indigenous myths, repurposed for the present day. For Kimmerer, these myths are important and relevant to our moment because they come from a time when people could still hear and interpret the teachings of “other species,” especially plants. The wisdom of plants, she writes, is

apparent in the way that they live. They teach us by example. They’ve been on the earth far longer than we have been, and have had time to figure things out. They live both above and below ground, joining Skyworld to the earth. Plants know how to make food and medicine from light and water, and then give it away.

Plants know, in other words, how to live reciprocally, and “we need to learn to listen.”

Behind this prescription is a direct case for narrative as the primary method of conveying the foundational ideas that shape a society’s imaginary. Drawing on Gary Nabhan’s construction, Kimmerer describes her project of ecological restoration as “re-story-ation.” Our relationship with the land we live on is “broken” because the dominant story we tell about it is in error. That story was brought by the immigrants from Europe to justify their domination, and it continues to inform our institutional structures and shape our responses to crisis (9-10, 31).

Kimmerer is not alone in this viewpoint. Agreement about the source and the time of the wrong-turning is widespread among those scholars concerned with ecological breakdown, mass extinctions, global warming—those scholars who see these matters as the meta-crisis, the broader habitat, so to speak, in which our political and social ills are nested, nurtured, and grow.

Writing these words brings to mind a video clip presented at one of the hearings on the January 6, 2021 attack on the Capitol. This clip showed long-time, right-wing Republican Party operative Roger Stone taking the official oath for some militant organization. “I am a Western chauvinist,” Stone vowed, “and I refuse to apologize for creating the Modern World.” The way this militant group has chosen to articulate and perform the debate is crude, narrow, and toxic. Still, the group’s general reading of the history aligns, at least in broad terms, with those scholars who associate the de-legitimization of animist belief systems and the advancement and institutionalization of an extreme dualism with the rise of the modern world and the philosophies of the West.

Kimmerer, for her part, defends the practice of Western science. She defends its practitioners, for whom the actual work of science—of “revealing the world through rational inquiry”—is an “often humbling” and “deeply spiritual pursuit.” But Kimmerer makes a distinction between scientific practice and “the scientific worldview.” The latter uses the products of science and technology “to reinforce reductionist, materialist, economic and political agendas.” The scientific worldview is destructive because it sustains “the illusion of control” and “the separation of knowledge and responsibility.” Kimmerer’s “dream” is that “the revelations of science framed with an Indigenous worldview” will lead to “stories in which matter and spirit are both given voice” (345-46).

Who will tell these stories, Kimmerer asks (9). For me, someone who has invested so much time and much of his living in hearing, reading, and thinking about stories, that’s the intriguing question. What are these stories and where are they? Who will tell them? Who is telling them?

A version of this essay appeared in Society for US Intellectual History.

Self Mastery or Self Artistry

When the semester is in full swing and shrinking non-work-related reading time, a service called Audm, which shows up on my pod-catcher, delivers recorded readings of articles from publications such as The New Republic, The New Yorker, and The New York Times Magazine. Now I can “read” while driving, cooking, and doing chores around the house.

A recent selection was a February 2022 essay by Arthur C. Brooks, called “How to Want Less,” from The Atlantic. Content could not have better fit the occasion: Brooks’ piece was not too dense so as to make multi-tasking impossible, but also strewn with a wide range of references from the history of ideas. Sartre, Buddha, Aquinas. The “hedonic treadmill.” The Tao. How nice to make use of one’s education while also prepping for dinner. Brooks writes about his daughter in college. I have a daughter in college, too.

Granted, there’s not much new in Brooks’ argument. Human beings are wired to seek satisfaction, and yet the very same wiring makes satisfaction impossible to achieve. “We crave it, we believe we can get it, we glimpse it and maybe even experience it for a brief moment, and then it vanishes.” It’s “the greatest paradox of human life.”

Before she went away to school, Brooks explained the situation to his daughter, and she found the prospect gloomy. He assured her that happiness was nevertheless possible. We have millenniums of human wisdom to draw upon, the intellectual work of those who’ve confronted the paradox, artists and philosophers, scholars and social scientists, and sages both religious and secular. If inner craving is unquenchable, we can achieve a kind of happiness via “free will and self-mastery” and the help of ideas.

Good advice! “The key to life is a low overhead” has been my preferred version of the basic maxim. Fewer wants lessen the need to labor for wages. Yet there was something in Brooks’ construction that, well, left me a little unsatisfied.

One of the reasons Brooks’ presentation is so familiar is how heavily it leans on “evolutionary biological imperatives.” Brooks calls on the age-old struggle of mind over matter, intelligence versus “several millions of years of evolutionary biology,” “a battle against our inner caveman.” This way of framing the paradox emphasizes the separation between mentality and physicality so favored by modern Western thought. A common thread among many scholars of the ecological imagination is that this “great separation” is at the root of our interrelated emergencies: environmental, economic, social, and political. Do Brooks’ constructions work to reinforce the mind/body, modern/primitive separation? Do they reproduce the dominant, underlying conception that nature and the body are governed by blind, material forces and that the human mind is an immaterial ghost that longs to break free from the physical?

I don’t know—it feels like a quibble. Life couples symbolic and material systems, and there is a real distinction between them, despite how interrelated they are. And certainly, plenty of thinkers within the ecological tradition find a relationship, as Brooks does, between freedom and self-restraint. Prince Kropotkin, Tolstoy, William Morris, Gandhi, Lewis Mumford, and Paul Goodman are among those Theodore Roszak includes within a “subterranean tradition of organic and decentralist economics” in his 1973 introduction to Small is Beautiful by E. F. Schumacher. Of course, Schumacher could be included on the list, as could Ivan Ilych and Cornelius Castoriadis. Similarly, and more recently, Giorgos Kallis, degrowth advocate and author of Limits (2019), writes that freedom is “not the unobstructed pursuit of desires.” It is the “conscious reflection on” and “mastery” of them (105).